Disclaimer

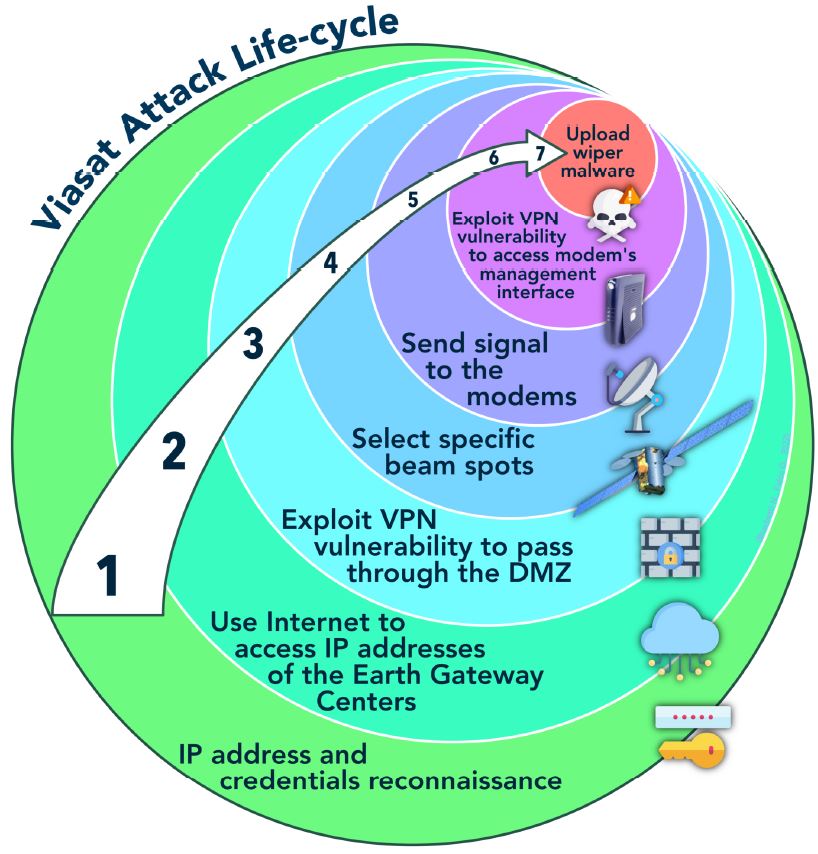

To do this analysis of the Viasat cyber attack, I used the open-source intelligence (1) of the team composed by Nicolò Boschetti (Cornell University), Nathaniel Gordon (Johns Hopkins University) and Gregory Falco (Cornell University). In their open-source intelligence, they reconstructed the lifecycle of the attack. They specified that however, without first-hand knowledge of ViaSat’s systems, they cannot be certain about their hypothesis. With their open-source intelligence, they schematized the entire attack lifecycle in a diagram.

Viasat’s statement (2) on Wednesday, March 30th, 2022 provides a somewhat plausible but incomplete description of the attack.

In a statement disseminated to journalists (3), Viasat confirmed the use of the AcidRain wiper in the February 24th attack against their modems.

At the DefCon 31, Mark Colaluca and Nick Saunders from Viasat presented a talk named “Defending KA-SAT“. During this talk, they argued not to believe everything that you can read on the internet. It’s often simply inaccurate. They told that there is no evidence or proof of the claims. There is no evidence of any compromise or tampering with Viasat modem software or firmware images and no evidence of any supply-chain interference. Regarding, the possibility that wipermalware was deployed and erased the hard drives of the modems, they answered that modems don’t have hard drives.

At the Black Hat USA 2023, Mark Colaluca , Craig Miller , Nick Saunders , Michael Sutton , Kristina Walter from Viasat presented a talk named “Lessons Learned from the KA-SAT Cyberattack: Response, Mitigation and Information Sharing“. This presentation will provide the most detailed public presentation of the KA-SAT event. Viasat will share the story of how it responded and performed a rapid forensic on several impacted terminals. This presentation will explain details around the forensic analysis that have not previously been publicly shared by Viasat, as well as the process of reverse engineering the malicious toolkit to verify it would produce the observed flash memory effects. Both Viasat and NSA will offer their lessons learned from the cyberattack and advise on how commercial and government organizations can follow this model to partner both in response to and preparation for future attacks.

Introduction

In this article, we will go through the Viasat cyber attack that occured on 24 February, 2022. The goal is to do a modelisation of this attack based on the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

The first question will be to explain why to use the MITRE ATT&CK framework to do this analysis while there are others frameworks and methodologies that can be used for the space sector.

The next work will be to identify Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) from the MITRE ATT&CK matrix that have been used by the hackers during the Viasat attack. To learn more about the MITRE ATT&CK framework, you can go to this article about the ATT&Ck v13 release.

Once TTP identified, we will map the TTPs on the ATT&CK Navigator in order to have the complete attack chain as a cyber kill chain.

About the Viasat hack in brief

The Viasat hack was a cyberattack on American communications company Viasat affecting their KA-SAT network, on 24 February, 2022.

Thousands of Viasat modems got hacked by a “deliberate … cyber event”. Thousands of customers in Europe have been without internet for a month since. During the same time, remote control of 5,800 wind turbines belonging to Enercon in Central Europe was affected.

According to Viasat, the attacker used a poorly configured virtual private network appliance to gain access to the trusted management part of the KA-SAT network. The attackers then issued commands to overwrite part of the flash memory in modems, making them unable to access the network, but not permanently damaged. The satellite itself and its ground infrastructure were not directly affected.

About Viasat

Viasat is an American communications company based in Carlsbad, California, with additional operations across the United States and worldwide. Viasat is a provider of high-speed satellite broadband services and secure networking systems covering military and commercial markets

Which framework using ?

The first question is which framework to use to do this analysis ? At this time, there are 5 frameworks and methodologies that can be used for the space sector :

- MITRE ATT&CK is a globally-accessible knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques based on real-world observations. You can learn more about MITRE AT&CK in our article here.

- SPARTA is the Aerospace Corporation’s Space Attack Research and Tactic Analysis. SPARTA is an ATT&CK® like knowledge-base framework but for Space Missions. SPARTA matrix is intended to provide unclassified information to space professionals about how spacecraft may be compromised due to adversarial actions across the attack lifecycle. You can learn more about SPARTA in our article here.

- SPACE-SHIELD is the Space Attacks and Countermeasures Engineering Shield from ESA. SPACE-SHIELD is an ATT&CK® like knowledge-base framework for Space Systems. It is a collection of adversary tactics and techniques, and a security tool applicable in the Space environment to strengthen the security level. The matrix covers the Space Segment and communication links, and it does not address specific types of mission. You can learn more about SPACE-SHIELD in our article here.

- TREKS is the Targeting, Reconnaissance, & Exploitation Kill-Chain for Space Vehicles Cybersecurity Framework. TREKS is a new Cybersecurity Framework that highlights the unique kill chain for the space vehicle. It’s a Cybersecurity Framework released by Dr. Jacob Oakley after more than five years spent researching and working on space system cybersecurity. You can learn more about TREKS in our article here.

- SpaDoCs, or the Space Domain Cybersecurity Framework, is a comprehensive and systematic model designed to address cybersecurity challenges in the space domain. Developed to bridge the gap between space and cyber domains, SpaDoCs aims to enhance collaboration and information sharing across mission, company, international, and government boundaries. You can learn more about SpaDoCs in our article here.

I did a quick comparaison in this article, of all the released Cybersecurity Frameworks for Space Sector

SPARTA is a framework but for spacecraft and space missions. SPARTA doesn’t cover ground segment. The entire Viasat attack took place on Earth, on a ground-based network and on a conventional information system. So, there is no reason to use SPARTA, SPACE-SHIELD or TREKS. MITRE ATT&CK is a great framework, well suited for this analysis. To be more precise, we used the MITRE ATT&CK – Enterprise Matrix.

Quick overview and comparaison between MITRE ATT&CK and the Cyber Kill Chain

What is the Cyber Kill Chain?

“The cyber security kill chain model explains the typical procedure that hackers take when performing a successful cyber attack. It is a framework developed by Lockheed Martin derived from military attack models and transposed over to the digital world to help teams understand, detect, and prevent persistent cyber threats. While not all cyber attacks will utilize all seven steps of the cyber security kill chain model, the vast majority of attacks use most of them, often spanning Step 2 to Step 6.” (source : netskope.com)

What is in the MITRE ATT&CK Matrix?

“The MITRE ATT&CK matrix contains a set of techniques used by adversaries to accomplish a specific objective. Those objectives are categorized as tactics in the ATT&CK Matrix. The objectives are presented linearly from the point of reconnaissance to the final goal of exfiltration or impact.” (source : trellix.com)

Comparaison between the Cyber Kill Chain and the MITRE ATT&CK matrix

The table below compares the stages of the Cyber Kill Chain with those of the MITRE ATT&CK matrix

| Cyber Kill Chain | MITRE ATT&CK |

| Reconnaissance | Reconnaissance |

| Weaponization | Resource Development |

| Delivery | Initial Access |

| Exploitation | Execution |

| Installation | Persistence |

| Command and Control (C2) | Privilege Escalation |

| Actions on objectives | Defense Evasion |

| Credential Access | |

| Discovery | |

| Lateral Movement | |

| Collection | |

| Command and Control (C2) | |

| Exfiltration | |

| Impact |

Mapping the Viasat hack with TTPs

To do this work, we mainly used 3 articles, documents or papers detailed below :

- [1] Space Cybersecurity Lessons Learned from The ViaSat Cyberattack from Nicolò Boschetti (Cornell University), Nathaniel Gordon (Johns Hopkins University) and Gregory Falco (Cornell University)

- [2] KA-SAT Network cyber attack overview by Viasat

- [3] AcidRain | A Modem Wiper Rains Down on Europe by SentineOne Team

Best Practices for MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

MITRE ATT&CK is often used to identify and analyze adversary behavior. CISA (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency) released a guidance to help analysts accurately and consistently map adversary behaviors to the relevant ATT&CK techniques as part of cyber threat intelligence (CTI)—whether the analyst wishes to incorporate ATT&CK into a cybersecurity publication or an analysis of raw data.

We used these best Practices for MITRE ATT&CK® Mapping that you can find here :Best Practices for Mapping to MITRE ATT&CK (cisa.gov)

Mapping the Viasat hack with TTPs

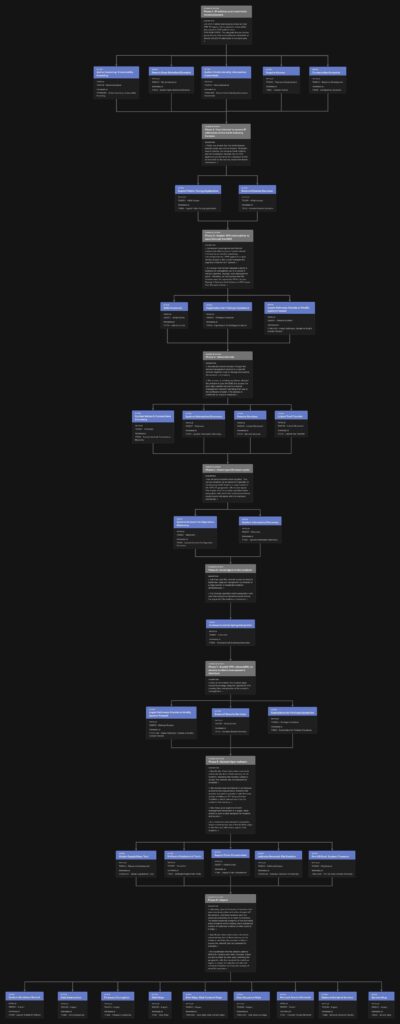

Through open-source intelligence, the team [1] composed by Nicolò Boschetti (Cornell University), Nathaniel Gordon (Johns Hopkins University) and Gregory Falco (Cornell University) reconstructed the lifecycle of the attack.

They specified that “however, without first-hand knowledge of ViaSat’s systems, we cannot be certain about our hypothesis“.

They schematized the entire attack life cycle in the diagram below (from document [1])

We will use this diagram to identify TTPs used by attackers at each steps of the attack

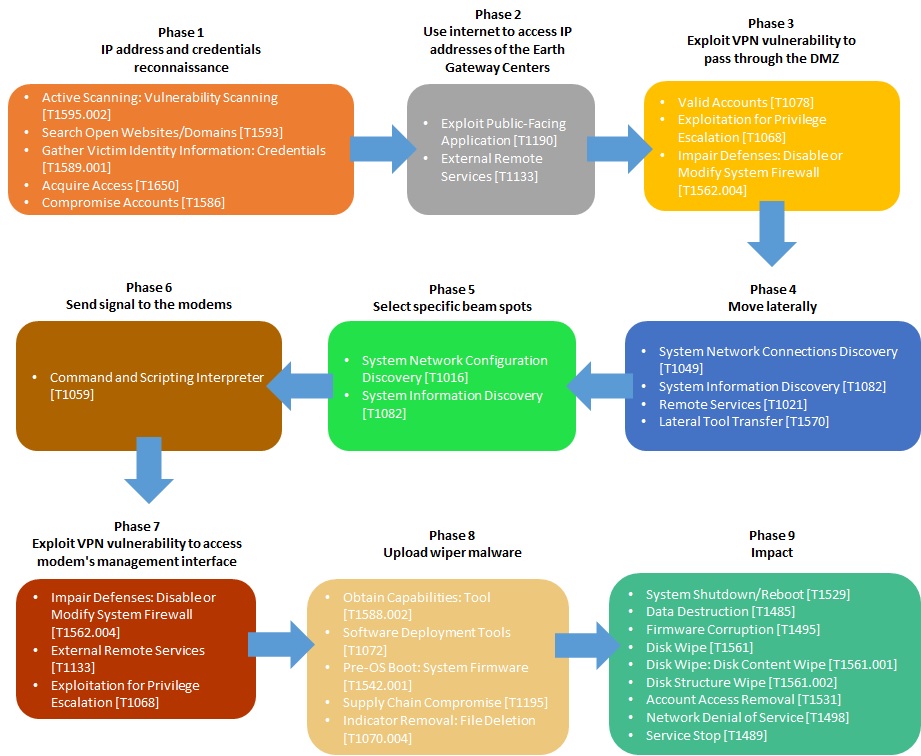

Phase 1 : IP address and credentials reconnaissance

[1] “In 2021, Fortinet disclosed an attack on their VPN “Fortigate” that exploited a vulnerability discovered in 2019 (editor’s note: CVE-2018-13379). The allegedly Russian hacker group Groove stole and published credentials of almost 500,000 IP addresses in the same year.”

At this phase, we identified the following TTPs :

| Tactic | Technique |

| Reconnaissance | [T1595.002] Active Scanning: Vulnerability Scanning |

| [T1593] Search Open Websites/Domains | |

| [T1589.001] Gather Victim Identity Information: Credentials | |

| Resource Development | [T1650] Acquire Access |

| [T1586] Compromise Accounts |

Phase 2 : Use internet to access IP addresses of the Earth Gateway Centers

[1] “ViaSat has shared that the initial attacker intrusion point was via the internet. Skylogic’s control servers, the Gateway Earth Stations, and the Surfbeam2 modems rely on VPN appliances produced by the company Fortinet as indicated by the security researcher Ruben Santamarta.”

At this phase, we identified the following TTPs :

| Tactic | Technique |

| Initial Access | [T1190] Exploit Public-Facing Application |

| [T1133] External Remote Services |

Phase 3 : Exploit VPN vulnerability to pass through the DMZ

[2] “Subsequent investigation and forensic analysis identified a ground-based network intrusion by an attacker exploiting a misconfiguration in a VPN appliance to gain remote access to the trusted management segment of the KA-SAT network.”

[1] “It is known that Fortinet released a patch to address the vulnerability, but it is unclear if ViaSat’s operator, Skylogic, ever deployed the patch. Therefore, we can surmise that the attacker used the unpatched VPN to access Skylogic’s Gateway Earth Stations or POP server from the open internet.”

At this phase, we identified the following TTPs :

| Tactic | Technique |

| Initial Access | [T1078] Valid Accounts |

| Privilege Escalation | [T1068] Exploitation for Privilege Escalation |

| Defense Evasion | [T1562.004] Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify System Firewall |

Phase 4 : Move laterally

[2] “The attacker moved laterally through this trusted management network to a specific network segment used to manage and operate the network” of modems.

[1] “This access, or privilege escalation, allowed the attacker to pass the DMZ and access the bent-pipe satellite intranet (the trusted management network) tunneling their way to the Surfbeam2 modem. This process is confirmed by ViaSat’s statement”

At this phase, we identified the following TTPs :

| Tactic | Technique |

| Discovery | [T1049] System Network Connections Discovery |

| [T1082] System Information Discovery | |

| Lateral Movement | [T1021] Remote Services |

| [T1570] Lateral Tool Transfer |

Phase 5 : Select specific beam spots

[1] “Not all ViaSat modems were targeted. This can be explained by an operator’s capability at the Gateway Earth Stations to select which of KA-SAT’s 82 geographic cells receive signal. This implies that the attacker specified which geographic cells (and their respective modems) would receive the signal with the malicious commands.”

At this phase, we identified the following TTPs :

| Tactic | Technique |

| Discovery | [T1016] System Network Configuration Discovery |

| [T1082] System Information Discovery |

Phase 6 : Send signal to the modems

[2] “and then used this network access to execute legitimate, targeted management commands on a large number of residential modems simultaneously.”

[1] “The attacker specified which geographic cells (and their respective modems) would receive the signal with the malicious commands.”

At this phase, we identified the following TTPs :

| Tactic | Technique |

| Execution | [T1059] Command and Scripting Interpreter |

Phase 7 : Exploit VPN vulnerability to access modem’s management interface

[1] “Once at the modem, the attacker again escalated privilege using the unpatched VPN, enabling their manipulation of the modem’s management.”

At this phase, we identified the following TTPs :

| Tactic | Technique |

| Defense Evasion | [T1562.004] Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify System Firewall |

| Initial Access | [T1133] External Remote Services |

| Privilege Escalation | [T1068] Exploitation for Privilege Escalation |

Phase 8 : Upload wiper malware

[2] “Specifically, these destructive commands overwrote key data in flash memory on the modems, rendering the modems unable to access the network, but not permanently unusable.”

[1] “The modem likely had limited or no firmware authentication requirements, therefore the attacker was able to provide a ‘valid’ firmware update, installing an ELF binary dubbed “AcidRain” which deleted data from the modem’s flash memory.”

[3] “The threat actor used the KA-SAT management mechanism in a supply-chain attack to push a wiper designed for modems and routers,”

[3] “In a statement disseminated to journalists, Viasat confirmed the use of the AcidRain wiper in the February 24th attack against their modems.”

At this phase, we identified the following TTPs :

| Tactic | Technique |

| Resource Development | [T1588.002] Obtain Capabilities: Tool |

| Execution | [T1072] Software Deployment Tools |

| Initial Access | [T1195] Supply Chain Compromise |

| Defense Evasion | [T1070.004] Indicator Removal: File Deletion |

| Persistence | [T1542.001] Pre-OS Boot: System Firmware |

Phase 9 : Impact

[2] “Ultimately, tens of thousands of modems that were previously online and active dropped off the network, and these modems were not observed attempting to re-enter the network. The attack impacted a majority of the previously active modems within Ukraine, and a substantial number of additional modems in other parts of Europe.”

[2] “Specifically, these destructive commands overwrote key data in flash memory on the modems, rendering the modems unable to access the network, but not permanently unusable.”

[1] “We hypothesize that the attack’s spillover effects in Germany and other European states are due to either an error when selecting the geographic cells that received the malicious signal, or simply the selection of cells that contained Ukrainian territory with overlap of other EU countries”

At this phase, we identified the following TTPs :

| Tactic | Technique |

| Impact | [T1529] System Shutdown/Reboot |

| [T1485] Data Destruction | |

| [T1495] Firmware Corruption | |

| [T1561] Disk Wipe | |

| [T1561.001] Disk Wipe: Disk Content Wipe | |

| [T1561.002] Disk Structure Wipe | |

| [T1531] Account Access Removal | |

| [T1498] Network Denial of Service | |

| [T1489] Service Stop |

Summary of MITRE ATT&CK TTPs observed in the Viasat cyber attack

The following table presents all TTPs that have been used by the hackers during the Viasat attack.

| Tactic | Technique | Description |

| Reconnaissance | [T1595.002] | Active Scanning: Vulnerability Scanning |

| [T1593] | Search Open Websites/Domains | |

| [T1589.001] | Gather Victim Identity Information: Credentials | |

| Resource Development | [T1650] | Acquire Access |

| [T1586] | Compromise Accounts | |

| [T1588.002] | Obtain Capabilities: Tool | |

| Initial Access | [T1190] | Exploit Public-Facing Application |

| [T1133] | External Remote Services | |

| [T1078] | Valid Accounts | |

| [T1195] | Supply Chain Compromise | |

| Execution | [T1059] | Command and Scripting Interpreter |

| [T1072] | Software Deployment Tools | |

| Persistence | [T1542.001] | Pre-OS Boot: System Firmware |

| Privilege Escalation | [T1068] | Exploitation for Privilege Escalation |

| Defense Evasion | [T1562.004] | Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify System Firewall |

| [T1070.004] | Indicator Removal: File Deletion | |

| Discovery | [T1049] | System Network Connections Discovery |

| [T1082] | System Information Discovery | |

| Lateral Movement | [T1021] | Remote Services |

| [T1570] | Lateral Tool Transfer | |

| Impact | [T1529] | System Shutdown/Reboot |

| [T1485] | Data Destruction | |

| [T1495] | Firmware Corruption | |

| [T1561] | Disk Wipe | |

| [T1561.001] | Disk Wipe: Disk Content Wipe | |

| [T1561.002] | Disk Structure Wipe | |

| [T1531] | Account Access Removal | |

| [T1498] | Network Denial of Service | |

| [T1489] | Service Stop |

The following table presents all TTPs mapped on the ATT&CK Navigator in order to have the complete attack chain as a cyber kill chain.

You can download the Excel version here.

You can also download the JSON file here and open it with the ATT&CK Navigator with the option “Open Existing Layer” and “Upload from local”

The following diagram presents all TTPs mapped on the entire attack life cycle of the Viasat cyber attack. This diagram is inspired from the schema of the entire attack life cycle done by the team [1] composed by Nicolò Boschetti (Cornell University), Nathaniel Gordon (Johns Hopkins University) and Gregory Falco (Cornell University).

Viasat Cyber Attack modeled with the MITRE Attack Flow Builder

Using all results of this work, I utilized the Attack Flow Builder to deconstruct the Viasat cyber attack, meticulously tracing each stage of the intrusion.

By systematically documenting the initial access vector, tracking lateral movement within the network, and visualizing the execution of the malicious firmware update, I created a detailed forensic map of the attack’s progression.

The full article about this work can be found here.

List of remaining work

Following this study, there is still a great deal of work to be done. See below for a list of topics still to be dealt with. If any of you are interested, please contact me here.

- Describing sequences of adversary behaviors in the Attack flow data model

- Trying to highlight the vulnerabilities exploited by the attackers

- Trying to propose countermeasures that could be used to mitigate the attack. Mitigation chapter for each techniques in the MITRE ATT&CK framework can be used

- Trying to map countermeasures on the MITRE D3FEND™ Matrix

Main References

- [1] Space Cybersecurity Lessons Learned from The ViaSat Cyberattack from Nicolò Boschetti (Cornell University), Nathaniel Gordon (Johns Hopkins University) and Gregory Falco (Cornell University)

- [2] KA-SAT Network cyber attack overview by Viasat

- [3] AcidRain | A Modem Wiper Rains Down on Europe by SentineOne Team

Others References

- Threat Intelligence Alert: Russia/Ukraine Conflict by NCCGroup

- Threat Update: AcidRain Wiper by Splunk

- New Sandworm Malware Cyclops Blink Replaces VPNFilter by CISA

- Mystery solved in destructive attack that knocked out >10k Viasat modems by Arstechnica

- VIASAT incident: from speculation to technical details by Reversemode

- AcidRain Wiper Suspected in Satellite Broadband Outage in Europe by Fortiguard

- NSA | Protecting VSAT Communications via NSA

- Strengthening Cybersecurity of SATCOM Network Providers and Customers by CISA

- Ukraine: Disk-wiping Attacks Precede Russian Invasion by Symantec

- Russia/Ukraine Update – November 2022 by Optiv

- Cyber Threat Handbook 2022 by Thales

- An Overview of the Increasing Wiper Malware Threat by Fortinet

- Characterizing Cyber Attacks against Space Systems with Missing Data: Framework and Case Study by Ekzhin Ear, Jose L. C. Remy, Antonia Feffer, and Shouhuai Xu – Department of Computer Science – University of Colorado Colorado Springs

- Wiper Malware: Purposes, MITRE Techniques, and Attacker’s Trade-Offs by Julian-Ferdinand Vögele (Threat Research @ Recorded Future)

- Best Practices for MITRE ATT&CK® Mapping by CISA

- Video Youtube : DEF CON 31 – Defending KA-SAT by Mark Colaluca and Nick Saunders

- Youtube Video : Black Hat USA 2023 – Lessons Learned from the KA-SAT Cyberattack: Response, Mitigation and Information Sharing by Mark Colaluca , Craig Miller , Nick Saunders , Michael Sutton , Kristina Walter